The Status of Portraiture in the 18th and 19th centuries

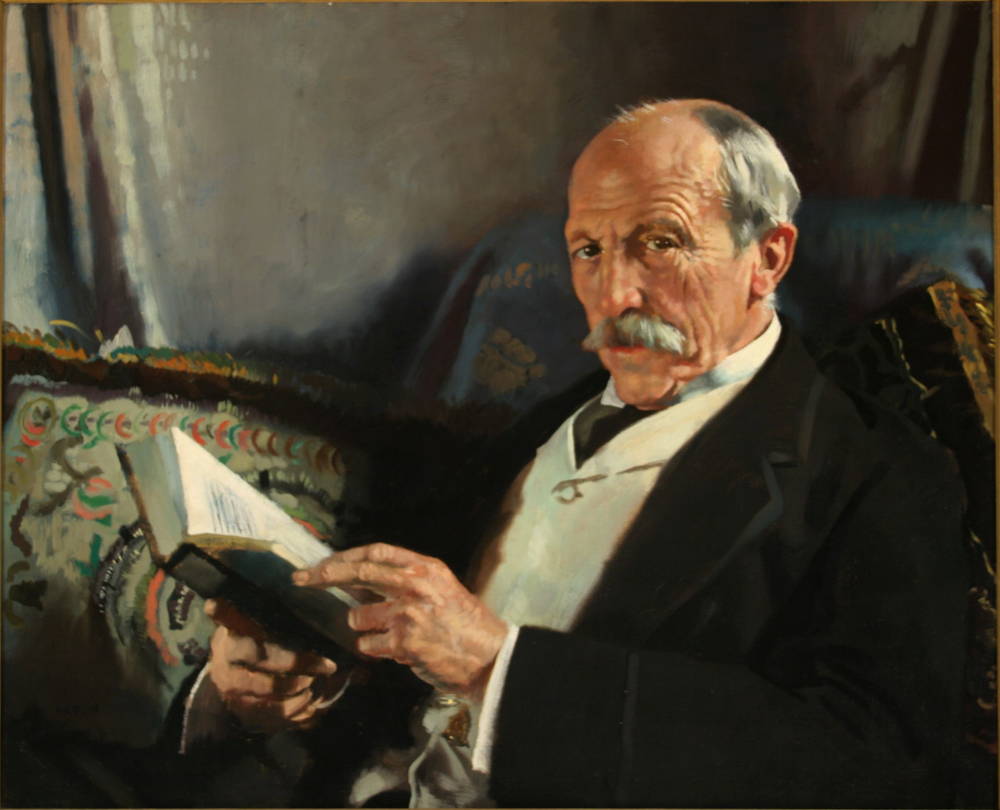

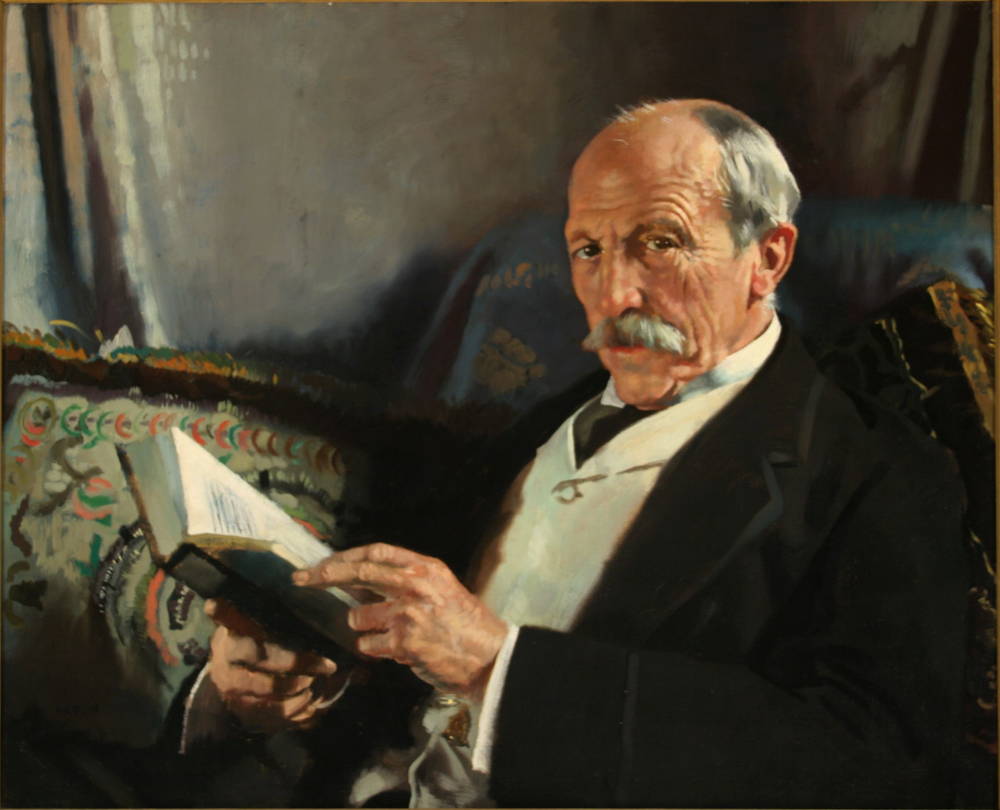

The great majority (21) of portraits in the Bailey collection are by 18th or 19th century artists. Only three date from the 20th century: Sargent's Portrait of Viscount Allenby [1784], and Orpen's Portrait of Rt. Hon. Lord Milner [1610], both paintings, and a watercolour Portrait of Cecil Rhodes [1771], by Mortimer Mempes. All the works are of the British school.

Portraiture in 18th and 19th century Britain could offer a secure and profitable career for the artist although throughout much of this period it would not have been regarded as the most important kind of painting that an artist might produce. Most respected was history painting, the painting of narratives from Classical history and mythology and of stories from the Bible. History painting was believed at the time to be the most challenging form of visual art, both for artist and spectator, because of its erudition and philosophical ambition. Portraits, along with still life and landscape and pictures of everyday scenes, were thought to be easier to produce and to understand because they were (naively) believed to be 'mere copies' of the world that confronted the artist's eye.

Portrait painters were often a little embarrassed about their chosen area of specialisation because of their belief in its inferiority to history painting. But in 18th century Britain, state and church patronage for history painting was almost entirely absent, so portraiture took its place as the main area of work for ambitious and respected painters. Joshua Reynolds [see 1600] was an interesting case of an artist who devoted most of his career to portraiture while remaining convinced of its inferiority to history painting. As director of the Royal Academy, he lectured art students on theoretical issues in the visual arts, and these lectures were gathered together as the still-famous Discourses on Art. In Discourse number three, this highly influential art theorist delivered a classic argument for the abstractness and resulting intellectual depth of history painting:

"If deceiving the eye were the only business of the art, there is no doubt, indeed, but the minute painter would be more apt to succeed: but it is not the eye, it is the mind, which the painter of genius desires to address…This is the ambition which I wish to excite in your minds: and the object I have had in my view, throughout this discourse, is that one great idea, which gives to painting its true dignity, which entitles it to the name of a Liberal Art, and ranks it as a sister of poetry".

Reynolds goes on to concede that there are many types of painting "which do not presume to make such high pretensions", and lists as examples the pictures of daily life beloved of Dutch seventeenth-century artists, battle-pieces, French Gallantries, landscapes and seascapes. "In the same rank", he adds, "is the cold painter of portraits". And yet the demand was for portraiture, and Reynolds was to make himself a master of the genre.

The solution to the conflict of interests was to approximate portraiture as closely as possible to history painting. It might be done by endowing a sitter with allegorical meaning, or by alluding, through pose, to celebrated Classical statuary. Costume was an important signifier and while some sitters might wear their own clothing, others might be clothed in garments from the past, very often drawn from the artist's own store of props (see Reynolds' Portrait of Lord Cardross [1600]). A favourite choice was loose drapery, designed to evoke the Ancient Greek and Roman past and generally convey a sense of timelessness, high culture and civilisation. Background props also played their part. Portraits usually focus the eye very deliberately on the face and figure of the sitter, leaving backgrounds undefined and minimal, but insofar as the sitter has a setting at all, it often includes a poetically weathery sky with little other than swags of drapery (see Hoppner's Portrait of Lady Ibbetson [1611]) or columns to accompany the figure. Both again evoke the Ancient world, the column, favoured in male portraits, symbolising rationality and civic humanism. The eighteenth-century British conviction that this society was the inheritor of Ancient greatness made these pictorial allusions particularly significant.

Sometimes, however, the British portraitist would follow Dutch precedent and produce images of the human figure that were robust rather than fancy. The Scottish school, represented by artists like Raeburn and Ramsay, was particularly drawn to this option. Raeburn's William Ferguson and his Son [1593] is a case in point. Here, Ferguson's boldly striped jacket and broad frame amply fill the picture space and give the resulting portrait an earthiness which seems entirely opposed to the 'dignified' portraiture called for by academic doctrine.

Pricing Portraits

Portraits were largely commissioned by - and of - the wealthy, and served to immortalise the patron or family members. While designed generally for the portrait galleries of private homes, portraits were often shown at public exhibitions or in small studio exhibitions before being moved to their final destination. In these public shows the artist was able to advertise his work and sometimes very widely. After the Royal Academy opened in London in 1769, it held annual exhibitions that drew large crowds and provided artists with career-boosting publicity.

Prices of works varied according to length and size, as well as being determined by the status of the artist. A patron might have a choice between a 'head', a 'three-quarter length' or a costly 'full-length' image. Full-length portraits, like Raeburn's Lt.Gen. Hay Macdowall [1589] or Lawrence's Poet Robert Southey [1586], were expensive commodities as well as being impressive visual statements. By the early years of the 19th century, an acclaimed portraitist like Lawrence was charging 200 guineas (one guinea was worth just over one UK pound) for a 'head', but approximately 800 guineas for a full-length portrait. To gain some sense of how much this represented, note that the average farm labourer, in the same period, earned approximately 20 guineas per year.

Originals and Copies

Portrait-painting in the 18th and early 19th centuries was a major industry. Often, a number of copies were made of a portrait, either for relatives of the sitter, or for friends and admirers. These copies were sometimes made by the original artist but were sometimes products of his 'studio', largely the work of assistants, with finishing touches by the master. In a world where paintings were often collaborative efforts, this kind of practice was very much taken for granted, in contrast to our modern anxiety about originality in art.

Many of the portraits in the Bailey collection constitute one of two or more versions of the same work. One example is Hoppner's Portrait of William Pitt [1582], probably largely the work of Reinagle Jnr. whom Hoppner employed to produce the many copies of the original that were suddenly commissioned on Pitt's death. Other examples from the collection are Portrait of Mrs Whitefoord by Opie or Hoppner [1624], three works by Raeburn, Portrait of Duke of Hamilton [1646], Portrait of Lt. Gen. Hay Macdowall [1589], Portrait of William Ferguson and his Son [1593], Reynolds' Portrait of Earl of Eglinton [1659], and Romney's Portrait of Lady Greville [1604].

|

Click here to view all portraiture

William Orpen, The Right Honourable Lord Milner, oil on canvas

Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of David Steuart Erskine as Lord Cardross, oil on canvas

John Hoppner, Portrait of Lady Ibbetson, c.1780-1790, oil on canvas

Thomas Lawrence, The Poet Robert Southey, 1828, oil on canvas

John Opie, Portrait of Mrs Whitefoord, oil on canvas

|