The Market for Reproductive Prints

Most of the prints in the Bailey collection are reproductive prints, that is to say they are produced by full-time professional printmakers and are copies of another artist's painting. They contrast with what are often called artist's prints where an artist has specifically chosen the medium of printing as a vehicle for his or her ideas and has created an original image in printed form. In the 18th and 19th centuries, there was a popular market for reproductive prints, a market that grew enormously in the early 19th century after the repeal of the glass tax made framed images much cheaper. This popular market for prints was largely brought to an end in the late century with the advent of photography. As the general interest in prints declined, however, specialist print collectors began to buy them and from 1880 to 1929, there was a boom in the print collecting market. This was probably the period in which Bailey built up his collection.

Although their work was enormously popular, reproductive printmakers struggled to gain official acceptance as serious artists. The claim was that their skill was a manual craft rather than an art form, and that since they reproduced others' images, their prints lacked all original genius. The printmakers countered this with the argument that any reproduction by hand involves multiple aesthetic choices as to style and technique that make the 'copy' far from a slavish one. Engraver John Landseer made the point, "Engraving is no more an art of copying Painting, than the English language is an art of copying Greek or Latin. Engraving is a distinct language of Art: and though it may bear such resemblance to painting in the construction of its grammar as grammars of languages bear to each other, yet its alphabet and idiom, or mode of expression, are totally different."1 This characterisation perhaps bordered on overstatement, but it was an important corrective to the painters' prejudice.

Despite the official prejudice, the reproductive print-maker in the 18th and early 19th centuries could enjoy a long and successful career. Examples represented in the Bailey collection are Bartolozzi [1566] and Woollett [1563 set and 1564 set] who both enjoyed considerable fame and financial success, both at home and abroad, reproducing the work of others. It needs to be remembered that while the modern tendency is to crave uniqueness in art, the artist of this period very often had a healthy interest in producing as many good copies as possible of his successful pictures. He realized that by distributing these copies - printed copies - as widely as possible, his name would be more widely known, his fame increased.2 As an example, Reynolds made extensive use of the services of reproductive print-makers, knowing that while an original Reynolds portrait might disappear from public sight into a private collection, the printed reproduction of it would ensure its continued life in the public sphere, and keep alive his fame.

Soon after returning from Europe and setting up a London studio in 1753, Reynolds became aware of the work of the print-maker James McArdell, himself recently (1747) arrived from Ireland. It was exposure to prints by the English-based artist, Godfrey Kneller, that had partly motivated Reynolds' original interest in art, and once established himself as a trained painter, he did not forget the tremendous power of reproductive prints to awaken interest in paintings. He commissioned McArdell to produce printed copies of a number of his works, and profited enormously from the fame that they helped bring him, acknowledging his awareness of this by painting a portrait of McArdell and declaring "by this man I shall be immortalized".3

McArdell and fellow print-makers from Ireland (known as The Dublin Group) were the chief engravers of Reynolds' work in his early career. After McArdell's death in 1765, Reynolds continued to employ Irish-trained print-makers, James Watson (perhaps a pupil of McArdell's) being a particular favourite. By the late decades of the century, however, a new generation of English print-makers had established themselves, Valentine Green and John Raphael Smith being among the most celebrated. Green's portfolio, Beauties of the Present Age, a set of nine prints after Reynolds' portraits, became among the most popular prints of the century. Here was a case of the print-maker seeing lucrative possibilities in the painter's work unseen by the painter himself; Green had noticed the success of a set of prints after portraits by Kneller (published as Beauties of Hampton Court) and felt sure that a group of portraits by Reynolds could be packaged and sold with similar success. So it was Green who approached Reynolds, the result being that the painter agreed to let a group of portraits not originally intended in any way to form a set to be offered in print form as such.4

In the Bailey collection, one Reynolds portrait, that of Lord Cardross [1600] is represented in print form [1572] also, the printmaker in this case being John Finlayson, best known for his long professional involvement with artist Johann Zoffany. It is possibly one of the many commissioned by the sitter (see footnote 4) who, delighted with the original portrait, ordered copies and prints to be produced from it. One other portrait in the collection, Gainsborough's Lavinia [1585], is represented in the original and in the print [1566]. This is a very interesting example of a painting being commissioned, along with others, precisely in order to provide original images from which a set of prints could be produced, the print set being the original inspiration [see 1585].

Text in Prints

Print-making was a complicated process, the product of a busy workshop. More than one specialist craftsman might work on a plate. Sometimes, one printmaker might engrave the figures and another the landscape background within the same picture, as in the prints by Neagle and Peltro in this collection, where Neagle produced the figures and Peltro the landscape [1765; 1766; 1767, 1768]. Often, a specialist colourist would colour the prepared print by hand. And the inscription under the image, produced in fine 'copperplate' handwriting, would often be the work of another specialist. This inscription was intended as an integral part of the whole, providing names of depicted characters or clarifying the image's meaning with supporting literary quotation [1563 set].

The left and right-hand bottom corners of the print margins offer important information about the production process. Here are given the name of the printmaker, the name of the artist whose work the print reproduces, and the name of the print publisher, plus date of publication. Del. , commonly seen, is short for 'delineavit' and means 'drew'. It refers to the producer of the drawing from which the printmaker is working. This drawing might be a copy of a painting and be an intermediate translation of the original, done specially for the printmaker to work from. It was often produced by an employee of the print firm, rather than by the artist who had produced the original painting. Pinx. or Pinxit means 'painted' and refers to the producer of the original painting. Sculp. Is an abbreviation of sculpsit and means 'engraved'. It gives the printmaker's name.

Printing techniques represented in the Bailey Collection

Mezzotint

Click here for all mezzotints in the collection

The print technique most favoured for the reproduction of 18th century portraiture was mezzotint.

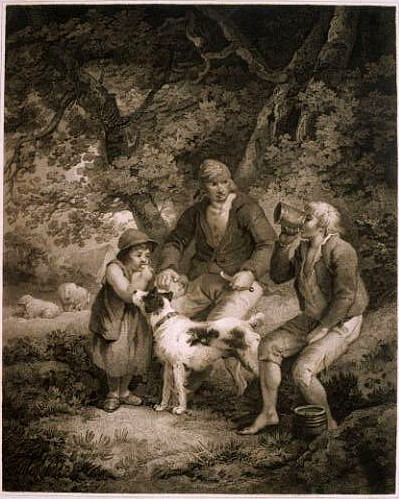

Mezzotint was developed in the 17th century and, as its name suggests, was suited to the reproduction of soft, shadowy half-tones. The image was created by a rocking tool with a curved, serrated edge, which was rocked all over the plate to roughen the entire surface. Thus roughened, the plate would print a rich black. To create light areas, the printmaker would scrape away the roughened surface with a burnisher. Mezzotint is the only print technique which works thus, from dark to light. It particularly suited 18th century portraiture, which typically employed shadowy undefined areas for background effects, but it was often used to reproduce smaller-scale narrative art also [1779, 1780].

Stipple

Click here for all stipples in the collection

Stipple, an 18th century invention, offered a fast method for establishing half-tones and had a decorative quality similar to pastel drawing. It was developed from the 'crayon manner' technique popular in France. It thrived in the 18th century because it well suited the gentle boudoir pictures that were much in demand among women; as a result, it was referred to disparagingly by many as a 'feminine' print technique. Stipple effects were created by finely punching the copper printing plate all over with tiny dots. Many of the craftsmen who did this stippling work had previously been producers of the decorative shoe buckles which had long been in fashion. When the craze for these shoes finally came to an end, the buckle-makers sought work in printmakers' workshops where they transferred their skill to the printing plate. Stipple worked well on a small scale and allowed for a much larger print run than was possible with mezzotint. For this reason it often replaced mezzotint, although the latter was generally used for the reproduction of formal portraiture and history painting.

Steel Engraving

Click here for all steel engravings in the collection

Steel engraving was an early 19th century invention. By engraving on an electro-plated copper plate, the printmaker was able to pull many more prints from the plate before it deteriorated. Also, it was possible on steel to engrave lines far more closely and regularly. The method was commercially useful, but it was criticised by purists for producing an image whose lines seemed mechanically uniform and whose overall tone seemed too 'grey'.

Softground Etching and Aquatint in Alken's Sporting Prints

Click here for all Henry Alken's prints

Many of Alken's sporting prints were produced by the artist himself, using the techniques of soft-ground etching and aquatint. Soft-ground etching offers an almost perfect reproduction of a chalk or pencil drawing. To produce the image, an etching ground is used to which tallow has been added, ensuring that the ground remains soft. Paper is pressed onto this ground and the drawing made on top of it. On being pulled away, the paper removes the areas of soft ground where the pencil has pressed onto the plate, leaving an excellent facsimile of the original drawing. The process continues as for normal etching.

Aquatint emerged as a technique in the late 18th century. As its name suggests, it allows for reproduction of the effects of watercolour. It is produced by sprinkling the plate with minute particles of acid-resistant resin which, when the acid bites round them, give an effect of a soft grainy texture and tone. It cannot produce line, however, so is often used in conjunction with etching, the aquatint ground being laid after the etched lines have been established.

Once invented, aquatint quickly became the technique of choice for many book illustrators. Combined with etching and hand-colouring, it could easily reproduce the 18th century watercolour style of transparent washes over pencil drawing. Late 18th/ early 19th century Britain saw a great boom in colour-plate books on a wide variety of topics. The majority of the Alken prints in this collection would have been produced for the factual or amusing books devoted to fox hunting and horse racing that were so popular at the time. Most in this collection were published by Thomas McLean, a leading producer of humorous and sporting prints and the main publisher of Alken's work.

Etching and the Work of Printmaker Frank Paton

Click here for all Frank Paton's work in the collection

To produce an etched image, a copper plate is covered with an acid-resistant ground made of gum, resin and wax. The image is drawn into this ground and then the plate lowered into a bath of acid which bites away the metal lines exposed by the etching tool, revealing the original drawing. As in all print techniques, the lines are then inked and the copper plate pressed against damp paper, the original drawing thus being transferred, in reverse, to the paper. Expressive effects can be obtained by manipulation of the acid-biting process and the wiping of the plate, but alternatively the technique can be simply used to reproduce a pencil drawing, as with these prints by Paton.

Frank Paton was a successful painter as well as illustrator whose etched prints were sometimes originals and sometimes reproductions of the work of other artists. His work often features domestic animals and hunting scenes, both of which are seen in these images. All or most of these appear to be designs for Christmas cards, however. Christmas cards first appeared only in the mid 19th century but by the end of the century had become tremendously popular. Although some of the earliest designs for such cards were similar to those of today, Paton's designs suggest they could sometimes have a far more serious message. His are topical and sometimes satirical images which, either in the main image or in the vignettes, reveal a sharply critical view of current political events, including British colonisation of South Africa. Coming Events Cast their Shadow Before [1574-7] shows a vignette image of the South African flag, shadowed by the Union Jack, while in A Deep Dream of Peace [1574-15] two dogs sleep on a torn South African map. British aggression in Egypt is featured in A Merry Christmas to You [1574-11] with a reference to the 1882 Battle of Tel al-Kabir, while in British Interests [1574-16] three chained dogs strain to attack a small poodle and other predatory scenes fill the vignettes. In A Merry Christmas [1574-6], an image which perhaps reveals Paton's bleak view of human nature, a comical role reversal sees humans as exhibits and various forms of sealife as visitors.

Many of Paton's prints, as well as these cards, were published by Leggatt and Bros., the London dealers from whom Bailey bought much of his collection.

|

Thomas Gainsborough, Lavinia (The Milk Maid), colour stipple

Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of David Steuart Erskine as Lord Cardross, oil on canvas

Joshua Reynolds, The Earl of Buchan, mezzotint

George Morland, The Peasant's Repast, stipple engraving

|