Early Years

Sir Abraham (Abe) Bailey was born in Cradock in the Cape on November 6, 1864. His mother, Ann Drummond McEwan, was Scottish by birth while his father, Thomas Bailey, was fromYorkshire. Married in 1860 in South Africa, Thomas and Ann Bailey had four children, Mary, Abraham, Susannah and Alice, before Ann's premature death in 1872.

Soon after Abe Bailey's birth, the family moved to Queenstown and there the father set up in business as a wagon-maker and wool merchant. By the time of his wife's death he also owned a local hotel and what his son later described as a "large general dealers and liquor business".1 When Ann Bailey died, the young Abe Bailey was only seven years old. The shock of his mother's death, plus a difficult and distant relationship with the father prompted the young boy to run away from home for some months and spend the rest of the year with Dutch-speaking friends who lived nearby. Shortly after, his father sent Abraham and one of his sisters to attend a school near Keighley, Yorkshire, but the kindness shown to him by his adoptive family in the months after his mother's death was to be formative in his life-long sympathy for the Afrikaner cause and culture.

After Keighley, Abe Bailey went on to Clewer House school near Windsor but, rejecting his father's suggestion that he go on to university, left school at fifteen and found work with the London wool and cotton-trading firm of Spreckley, White and Lewis. Two years later he was back in South Africa, where he felt that fewer social constraints stood in the way of the aspiring self-made businessman. Initially he joined his father's business in Queenstown but in 1886 moved to Barberton, enticed by the stories of great fortunes to be made from gold mining. He had a difficult start, but in time began to enjoy great success as a stockbroker and financial agent. By 1894, he had become the head of what was called the Bailey Group of gold mines and had begun to establish himself as one of the chief mining magnates of the Witwatersrand. Via his business interests and his connection with Cecil John Rhodes, whom he met at this time, he acquired substantial mining and land properties in the former Rhodesia and by the thirties had become one of the world's richest men.

Life in Politics

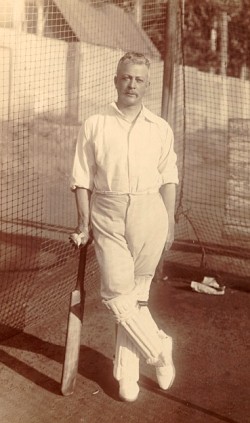

After their meeting in the late years of the nineteenth century, Rhodes quickly became something of a mentor to Bailey. Under his influence, Bailey became part of the group that formed the notorious Reform Committee that was linked to the Jamieson Raid. He was initially sentenced to imprisonment, then heavily fined instead for his complicit involvement in the Jameson Raid, but went on to pursue an active political life in government. On Rhodes' death in 1902, Bailey became Member of Parliament for his friend's former seat of Barkly West, and then in 1908, represented Krugersdorp in the first elections of the Transvaal Parliament. In the First World War, he served as Deputy Assistant Quartermaster-General to the South African forces and was involved in recruiting men for the army. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre by the French government and a baronetcy by the British one in recognition of these services.

Bailey spent a good deal of his life commuting between South Africa and Britain, where he had a home in Bryanston Square, London and in East Grinstead, Sussex. This arrangement, combined with his wealth and influence, (the latter aided by his second marriage, in 1911, to Mary Westenra, daughter of the fifth Lord Rossmore of Monaghan) allowed him to play a part in British political life also. He was awarded a baronetcy for services rendered during the First World War,2 while his London home was a venue for some important political arbitrations. The meeting of December 1916 which resulted in Lloyd George replacing Asquith as British Prime Minister took place at Bryanston Square, while discussions that helped bring to a close Britain's General Strike of 1926 were held here also. There were frequent social gatherings too, where guests included Smuts and Churchill, a particular friend of Bailey's, and a number of other leading British political figures.3

Bailey seemed to have had a talent for facilitating negotiations between opposing political groups. Back in South Africa, he would invite to the same parties men as politically diverse as Hertzog, Botha, Smuts, Duncan and Jameson, and manage to 'soften personal resentments'4 if not more theoretical points of difference. It was done in an unforced way, helped along by Bailey's genuine amiability and generosity.

It helped that Bailey was personally convinced of the need for common ground to be found between the Afrikaner and the British, a conviction which lay behind his sponsorship of the Union Club movement and its journal The State. His strong emotional commitment to South Africa was also a strength. Thanking the country for giving him social mobility, a feat much harder to achieve in the England of the day, Bailey told a gathering in 1930: "I did not come out of the top drawer. I am the son of emigrants. My parents went to South Africa and there I was born, and I love South Africa with all my heart, . . . for it was in that country . . . that I was able to rise from the bottom of the ladder."5 His son James remembered that he often used to dwell on his humble origins and subsequent rise through the ranks, repeating the refrain that he was "a self-made, self-made man".6 It was a thought which seems to have kept the father grounded and should perhaps be related to his love of the country life, whether in South Africa or in Britain.

The Country Life

In South Africa, Bailey owned a farm estate in the Hantam district, near Colesberg, which comprised forty farms covering an area of 300 square miles. Here he bred sheep and became one of the major racehorse breeders in South Africa and a steward of the South African Jockey Club for thirty years. His name was well-known in British and South African racing calendars for many years. It has been estimated that, during his lifetime, Bailey won the prestigious Johannesburg Handicap as least twice as often as any other owner, while during the same period horses of his such as Foxlaw, Son-in-Law, Tiberius and Dark Ronald achieved great success on the British turf.7 Bailey took a countryman's pride in his horses, but made fortunes out of their success too. He unashamedly confessed to his love of gambling, on horses or indeed on anything, provided it was on a large and daring scale:

"All my life I have been a gambler. I have not in mind the meaningless habit of putting a pound or two on a horse and waiting for a jockey to pull it first past the post. That's just feeble fumbling with fate. I mean going all out on something which may yield big returns in life - love, politics, everything that touches human activities: but always be guided by a sound knowledge of what is possible (even though seemingly in the realm of the miraculous), and what is not possible. The chances against success may be terrifying, but if you have got the gambler's instinct, the more nearly they are terrifying, the more fascinating they become. That is your gambler." 8

It was an impulse which netted him the largest sum ever made at Johannesburg's July Handicap when his horse Lovematch won 64 000 pounds. But his interests were not confined to horses. He was a keen boxer, in the days when the sport had a different status to its current one,9 and was also an enthusiastic supporter of South African cricket and a member of the Transvaal eleven. Meanwhile in Britain, where he spent a good deal of his time (it was estimated that by 1936 he had travelled between Southern and Northern hemispheres a hundred times), he was a keen participant in fox hunting and pheasant shooting as well horseracing. Indeed, in recognition of these interests, Bailey used to arrive in Britain in time for the famous Derby, and leave at the end of the pheasant shooting season.

Last Years

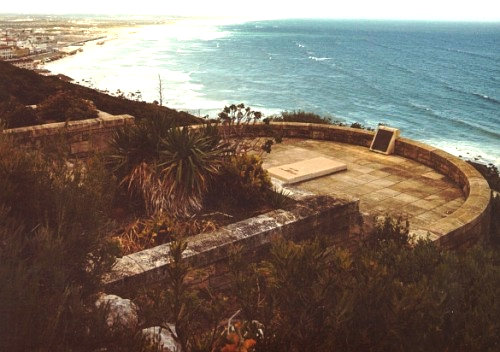

It was, then, a life of great good fortune, in which city business activity was interspersed with the largely rural sporting activity of the traditional landed gentleman. But Bailey's life was not without its personal setbacks. His first wife, Caroline Paddon, whom he married in 1894, died in 1902, leaving a son and a daughter. In 1924 Bailey himself began to suffer ill health and was diagnosed in 1929 with thrombosis. By the mid 30s, this condition had seriously advanced, causing Bailey extreme pain. In 1937, his left leg had to be amputated, and in the following year, the other leg was also removed. Bailey showed a salutary wit and lack of self-pity about his new condition. Turning down an invitation to the opening of Rhodes' birthplace as a national museum in 1938, he was able to quip "I am sorry I cannot rise to the occasion and be with you, as my legs have not yet grown again".10 He died at his Muizenburg home two years later, and was buried on the Muizenburg hillside.

Public Benefactions

In his lifetime, Bailey made some important public benefactions. In 1936, motivated by his second wife's passion for aviation, he donated 10 000 pounds to foster the development of aviation in South Africa.11 On a larger scale, in 1925 he presented the Fairbridge Collection of some 15 000 volumes of Africana to the South African Library and provided a special wing in which to house it, and in the early twenties gave 100 000 pounds to the Royal Institute of International Affairs in London to secure its future. In 1923, it moved into Chatham House and five years later Bailey promised the institute another 5000 pounds per annum (then half its total running costs) in perpetuity. Meanwhile, in his will he provided for the creation in South Africa of the Abe Bailey Trust, the aim of which was to finance initiatives by which British and Afrikaans South Africans might "work together wholeheartedly in devotion to the interests of their [sic] common country."12 He also bequeathed to the South African National Gallery his large art collection. 13

When Bailey died in 1940, the Second World War was underway, and it was hardly possible to transport his sizeable bequest to South Africa. Instead, it was moved, for its safety, from Bailey's London home to Candover Hall in Shropshire, where it waited out the war along with a number of other art collections. Once the war was over, it was shipped out, and the works arrived in November of 1946. They were hung in three newly-created rooms at the gallery, and the collection was officially opened by Smuts on 5 March 1947.

|

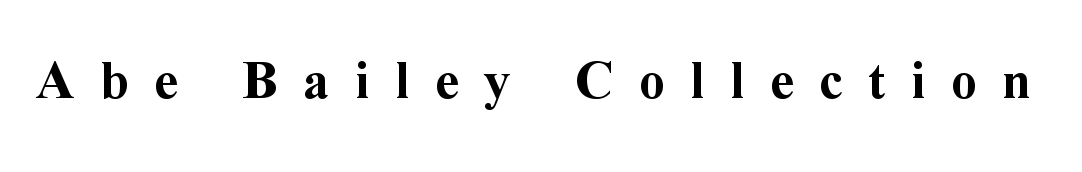

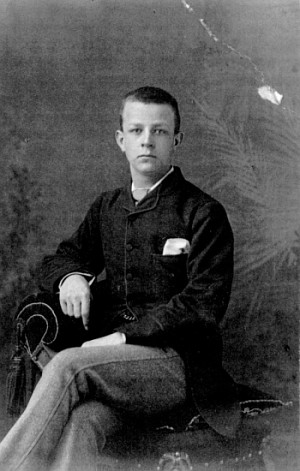

Young Abe Bailey

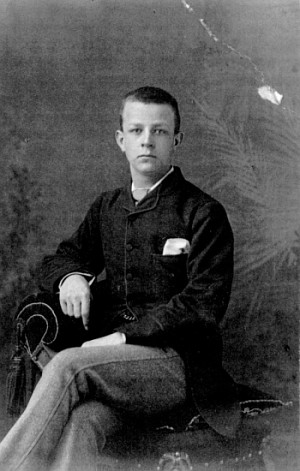

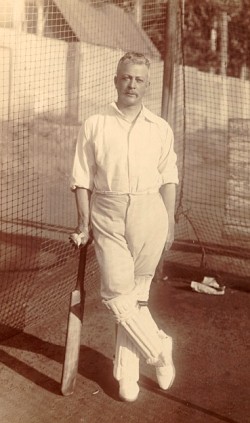

Bailey in the 1890s, captain of the Transvaal cricket team

Living room at 38 Bryanston Square. Portraits from the Bailey collection, including Romney's Portrait of Georgiana, Lady Greville [1604] hang on the wall.

38, Bryanston Square, W1, Bailey's London house. This was demolished after suffering major war damage in 1940, but the name lived on in the affluent suburb of Bryanston in Johannesburg, developed by Bailey.

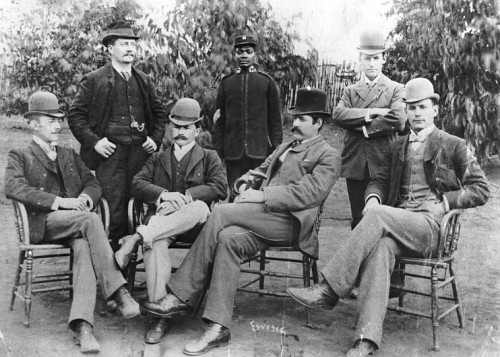

Bailey with fellow directors of Rhodes's Consolidated Gold Field mining compary, 1895. Back row from left: John Hays Hammond, unknown servant, George Farrar. Front from left: Alfred Beit, Lionel Phillips, Frank Rhodes (brother of Cecil), and Abe Bailey. This group was to form the core of the Reform Committee, instrumental in the notorious Jameson Raid.

Abe Bailey, double amputee, is carried from a trans-Atlantic liner. Throughout his life, Bailey commuted regularly between his homes in Britain and South Africa.

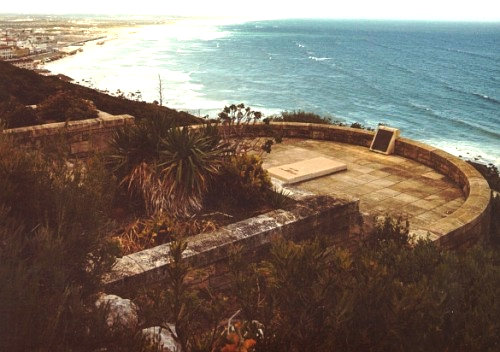

The memorial to Abe Bailey, on the mountainside above Muizenberg near Cape Town

|