Introduction

There is regrettably little evidence as to how and when Bailey bought the many works that make up his collection. What is clear is that his main advisor was Martin Leggatt, uncle of H.A.Leggatt of the now-defunct art dealers, Leggatt Bros of Piccadilly. We do not know exactly when the two met, but they seem to have known each other for some time before the First World War. 1 Unsurprisingly, most of the Bailey works appear to have been purchased by Leggatt Bros, but how much part Bailey played in their choice in unclear. So too is the question of when the works were purchased, as Leggatt's records were destroyed in the early 20th century.

The great majority of the paintings in the Bailey collection are by British artists. They range from the 18th century to the early 20th, and they are predominantly either portraits or sporting paintings. The choice of sporting paintings and prints is explained by Bailey's interest in the world of the countryside and horse sports (see below). The taste for portraiture - and portraits of figures quite unrelated to Bailey's own family - requires a little more explanation. Certainly it was not uncommon. In the period when Bailey was collecting - roughly 1890 to the mid-1930s - there was a widespread taste among newly-wealthy buyers for British portraiture of the 18th and early 19th centuries. The new American collectors, as well as their South African-based counterparts,2 bought eagerly in this field. And there was much available.

The South African collector and British portraiture

In the turn-of-the-century period, many valuable artworks from UK private collections were coming onto the market, a consequence of the 1882 Settled Lands Act. This act, passed to avert a crisis on the large English estates ruined by the rapid growth of the American wheat industry, declared that trustees of settlements could now sell off land and possessions provided that the proceeds remained under trusteeship. It ushered in a flood of sales on the London art market, with the Blenheim sale of 1884-5 one of the first most celebrated. It was a market rich in the 18th century English portraiture that had formed a staple of so many private collections in English country homes. 3

But the ready availability of this portraiture does not in itself explain the passion for it. Among a number of the American collectors (eg. Henry Clay Frick, Henry Huntingdon, and Benjamin Altman) as well as the South Africans, 18th century English portraits were particularly desirable acquisitions because they offered to the newly-rich of a young country the illusion of permanence and roots. It mattered little to a collector like Bailey that the portraits he collected (largely in the 1920s and 30s) were of people with no connection to himself or his family. They stood for Heritage, and for aristocratic grandeur, and offered an ideal to which one might aspire. Collecting such pictures helped one create a social identity. And it helped if these portraits evoked a classical past, as they so often did, through the use of strategic props and costume; classical references conferred status, on the original sitter, and on the latter-day collector.

Although the classical references used in 18th century English portraits would have increased the portraits' appeal to a collector like Bailey, it is noteworthy that classical art itself or indeed art of any type from France and Italy is not a feature of his collection. An exception is the pair of landscapes by French 17th century artist Gaspard Dughet [1597; 1598], and two works (although one of these is a horse study) by the 19th century French artist Meissonier [1678; 1742]. On the whole, the collection is northern European in character. This lack of work from southern European centers might be simply a matter of availability and price. Were Italian, French and Spanish works by the old masters simply too scarce - or too exorbitantly priced for a collector whose art collection was perhaps not a central preoccupation in his life? Were they not to the taste of Bailey's adviser-buyer, Martin Leggatt? Or not to the taste of Bailey himself? All of these seem to be possibilities, and again, are not unusual tendencies for the time. Among some of Bailey's contemporary US collectors, French painting, for example, was viewed with some mistrust, as "effeminate" or decadent. Henry Duveen, adviser to major US collector Benjamin Altman, advised the wealthy buyer against much that appeared at one notable sale, noting that "a great number of things were only fit for French taste, being all of a class which we call 'finicky' and effeminate, so much sought after by French people."4 The idea died hard among many American collectors that the most appropriate art for a manly, new nation was the art of northern countries - the Dutch and English in particular - and that the art of the Mediterranean pulled in the opposite direction. A tough self-made businessman like Bailey may well have shared these views.

Sporting art and Bailey's love of the countryside

By far the largest number of works in Bailey's collection fall into the category of sporting art. This is a broad term for a genre of art popular in England from approximately 1690 to 1850. The sports featured in this art might include cricket or boxing, both established and popular in the 18th century, but the ones most commonly seen in sporting art are horse sports, images of horse races (along with single portraits of the horses who featured in these), and those of hunting on horseback in the countryside. Other common themes of sporting art include that of game shooting, and the world of horse-drawn transport, subject of the coaching pictures. From early on in his career, and likely before he began his main portrait collecting, Bailey was buying sporting paintings and prints.5 He was motivated simply by a love of and identification with the world they represented, although it needs to be remembered that this world had to a large extent disappeared by the time Bailey was collecting, and relatively few artists were still working in the genre.

Sporting art offered essentially a nostalgic image of the rural world long-past, but this probably only endeared it further to Bailey. His own involvement in the life of the countryside was linked both to work and to leisure. He was a major landowner in South Africa and Rhodesia, owner of a number of large working farms in the Cape and a leading breeder of racing horses. He was passionately interested in horse racing,6 loved hunting and shooting and was additionally a keen cricketer. The fact that these interests were addressed by sporting art 7 led to his building up one of the world's largest private collections of the genre. However when, in the 30s, he was planning where to bequeath this collection, few galleries in Britain were interested in sporting art and bizarrely, it may seem, the pictures of rural England plus portraits of British dignitaries ended up at the National Gallery of South Africa.

The reception of the Bailey collection in South Africa

Abe Bailey's bequest marked the end of the era of large private benefactions to the SA National Gallery. Established in the 1870s and officially opened in its own specially-designed building in 1930, the gallery struggled with a meagre budget and a modest collection in these early years and was grateful for gifts from private collectors. It had already been augmented by the many works given by Alfred de Pass between 1926 and 1949,8 and also by the 1935-36 gift of Sir Edmund and Lady Davis's private collection,9 but the Bailey bequest was its largest single gift.

The promised arrival of the Bailey collection prompted the SA government to enlarge the National Gallery with four extra rooms in which the collection was then hung, but inevitably with time these rooms had to be used for other works as well and the Bailey collection competed for space with a growing permanent collection. A collection of the sporting art was gathered together for exhibition in early 1951, while another larger exhibition of this art was held in 1970, but political issues plus the pressure of modernist taste delayed any further large-scale exposure of the collection for a while. In recent years, there has been a change. A major exhibition of the whole collection was opened early in 2001 and ran for over a year.10 With a new, less exclusive art-historical canon allowing for the importance of 'minor' genres like sporting art, the gallery was able to showcase this considerable part of its permanent holdings, as well as many of the other genres and media in the Bailey collection. On an ongoing basis, too, the gallery shows selected works from the bequest as part of its exhibition of the permanent collection.

Bailey's Cape-based art collection

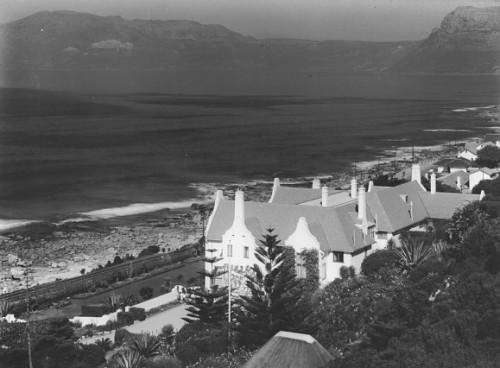

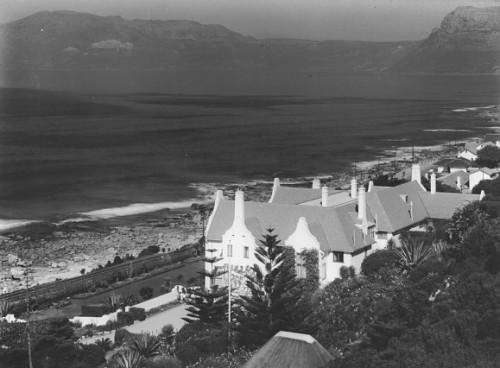

At his death, Bailey left a further art collection at his Muizenberg home, Rust en Vrede, just outside Cape Town. It differed significantly from the London-based collection. It was smaller in size, largely made up of prints and watercolours (though including some sculpture, entirely absent from the London collection), and heavily biased towards local scenes and artists. Many of the latter were 19th century figures, but later South African artists Anton van Wouw, Gwelo Goodman and Constance Penstone were also represented. A large painting of Bailey's Muizenberg home, by local artist G. Bevington, was part of the collection, as was a pencil drawing of Bailey himself by SA artist J. Anschewitz.

The collection and its arrangement give little sense of having been of really vital importance to Bailey. In the bedroom, where he spent many hours of his life at the end, there were 5 works dismissively described as 'assorted pictures' in the 1940 inventory and valued at no more than 6g in all. The reception and entrance rooms of the house contained a number of images of Rhodes, in various media; he was by far the most heavily-represented famous name. But there were none of the large Old Master portraits that formed a staple of the London collection, and no sporting paintings either, although a small number of sporting prints. Other prints, by Rembrandt, Whistler and Haden, display no overall thematic coherence, although they maintain - in line with the collection as a whole - the British/ Dutch emphasis that is a feature of Bailey's famous London collection also. In his much smaller and more modest Muizenberg collection, as in the London one, French and Italian art are not represented.

The Muizenberg collection was very much lower in monetary value than the London one. The London collection had been valued at over 30 000 pounds (by Leggatt bros in 1940), the Muizenberg one at under 2 000 pounds (by Charles Wiley of Cape Town, 3/9/1940 ),11 although in the event it sold for more than its valuation. It was auctioned in 1951. On the whole, the most sought-after works were the 35 works on paper by 19th century artist Thomas Bowler. These had been hung in Bailey's library, and included some valuable items, three of which were bought by Oppenheimer. The highest-selling work, a portrait of Lady Grey (wife of Sir George Grey) by William Gush, was sold for 340g to a Mr Harvey. A late 19th century painting, Inauguration of the Cape Town Breakwater by Thomas Baines, was bought by the Johannesburg Library for 245g, while two small bronzes, of Rhodes and Kruger, and a life-size bust of Rhodes also sold for a reasonable price. Apart from this handful of works, the rest realized less than 100g apiece.

Miscellaneous gifts and portraits of Bailey in public collections

A portrait of Bailey (1916) by P. de Laszlo was bequeathed to the Royal Institute of International Affairs. Another portrait of him, by Oswald Birley, hung in the SA Public Library (now the National Library of SA). Three group portraits commissioned by Bailey are in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in London.12 These are Some Sea Officers of the Great War, by Arthur Cope, presented by Bailey in 1921, Some General Officers of the Great War, by John Sargent, presented in 1922, and Some Statesmen of the Great War by James Guthrie, presented in 1930. Guthrie's work was the last he painted before his death in 1930. All the depicted men, with the exception of Lord Kitchener, sat individually for the artist in his London studio from 1920, when the work was begun. Guthrie is recorded as having worked on this portrait in consultation with the then-director of the gallery, J. D. Milner. The resulting work, measuring 13ft by 11ft, was the largest to date in the gallery's collection.

Bailey chose the artists for this project in consultation with his long-time advisor Martin Leggatt. He held a large banquet in late 1931, attended by the Prince of Wales, to host and commemorate all those surviving who appeared in these portraits.

|

Abe Bailey c.1890s

Bailey's Muizenberg home, Rust-en-Vrede, near Cape Town

|