The Genre of Sporting Art

Sporting art is a category term of fairly recent origin. At the time when these pictures were produced, they would simply have been called 'animal pictures'. But they are a particular kind of animal picture. They document the rural sports of fox-hunting and game shooting that were very popular in 18th and 19th century England. They also document the world of horse racing, and depict either the race events or the successful horses that ran in them. Commissioned by those who participated in hunts or who owned race horses, they would be hung in the owner's country house, either in the entrance hall or in special 'sporting halls' where meals were eaten before and after the hunt. Finally, some of these pictures are devoted to 'coaching' or horse-driven transport, a familiar sight until the arrival of the railways in the mid-19th century.

By the time Bailey began to collect sporting art, very little of this art was still being produced (see Munnings [1596; 1614; 1615] as an exception in this collection). It began to die out in the mid-19th century, as the world it documented disappeared. Industrialisation triggered a large-scale exodus from the countryside, and towns and cities became the vital centre of most people's lives. Sporting art had documented the importance of the countryside and the importance of the horse, but the focus was shifting away from both. Animal pictures continued to be produced in late 19th century England, but they tended now to be either emotionally charged images of animals in the wild, or pictures of animals in domestic interiors. The late Victorian artist, Edwin Landseer, is a well known exponent of these later types of animal imagery.

The Status of Sporting Art

In the 18th and 19th centuries, sporting art had a far lower status than portraiture within the art world and well into the 20th century it was a denigrated genre. Partly this has to do with the amateur status of many of the artists. Many of them transferred to painting from other, modest careers; Ferneley, for example, started out as a wheelwright, while Herring began his working life as a coach driver. Moreover, most of these painters underwent only a relatively simple workshop apprenticeship in their art. But another reason for sporting art's poor status before the 20th century was its 'low' or insignificant subject-matter; the fact that it focused upon animal life and had no aim other than to document appearances condemned it in the eyes of those looking for a higher intellectual content in art.

This genre, however, has enjoyed something of a revival in the last forty years. The interest shown in it by major American collector Paul Mellon helped boost its status, while the British Sporting Art Trust, established in the 1970s, has also promoted the genre and given it important publicity. Additionally, great changes in the academic study of art history have played a part. Art historians in the last few years have shifted their attention increasingly from the 'Great Masters' to works by minor artists and to pictures that are revealing of their societies' beliefs and values. Sporting art, with the excellent insight it offers into aspects of 18th and early 19th century society, suits these new art-historical interests. Viewed as social documents, sporting pictures tell us much about rural versus urban culture, and about attitudes towards rich and poor, and leisure and sport.

The Development of Horse Racing as a Sport

Horse racing began to emerge as a pastime of the wealthy in the late 17th century. New, Arab breeds of horse were being imported into Europe, and scientifically bred. These lean, swift thoroughbreds contrasted with the heavy, slow horses previously used for the farm and for sports such as stag hunting.

The horse race was originally a means of testing the speed and pedigree of these new breeds. In its earliest days, it was generally a contest between only two or three horses, with owners placing wagers as to which would win. The competing horses would run a series of one-mile (1.6 km) races and would be dried at the 'rubbing down house' [see 1607] in-between each race.

In the course of the 18th century, the races grew to include a larger number of horses, and they turned into a quite independent sport. Audiences grew, and the era of the professional jockey began. The world of horse racing was now a great social mix, with betting and gambling underpinning it. The horse owners, however, were keen to preserve distinctions between themselves on the one hand and the mass audience, the jockeys and the stable hands on the other. This was one of the motivations behind the formation of Jockey Clubs, which regulated the sport.

Horse Portraits

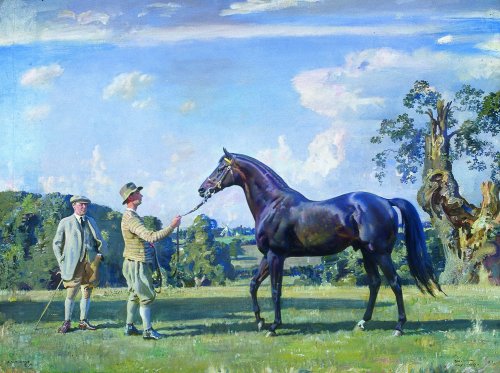

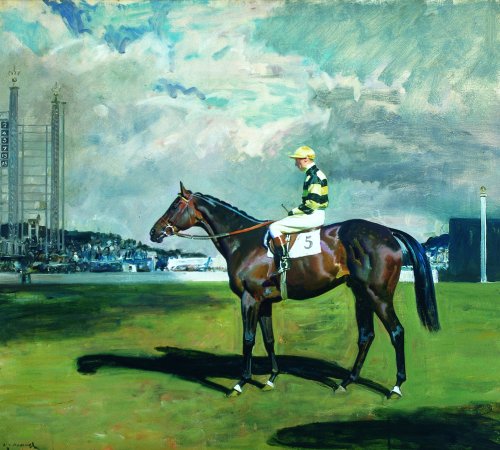

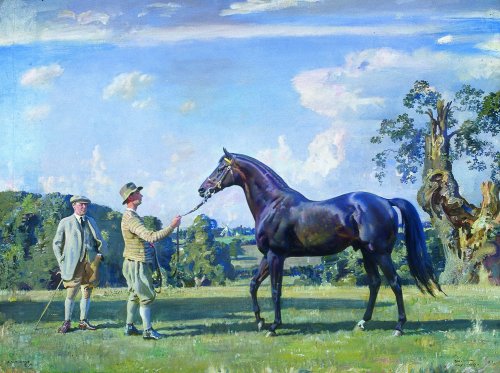

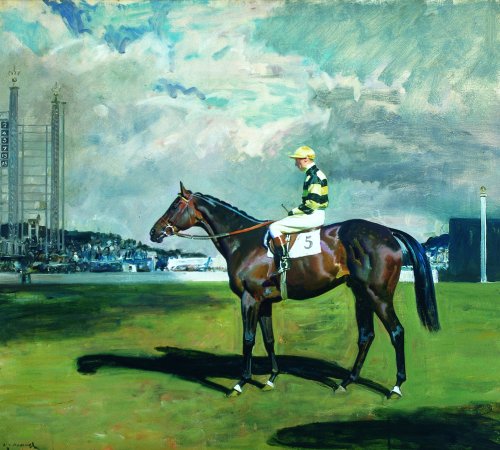

With the establishment of horse racing as a socially prestigious sport, the animals that ran these races came to be regarded as celebrities, and a kind of 'portraiture of the horse' evolved to document them. These horse portraits helped advertise the new scientific breeding programmes, and were also a boast on the part of the proud owners. George Stubbs was the 18th century master of this kind of horse portraiture but many others worked within the genre, into the 20th century. In the Bailey collection, the Munnings works Son-in-Law [1596], Foxlaw 1616] and Tiberius [1614] are all of winning horses bred and raced by Bailey.

'Warlike Exercises': the Development of Hunting

From the 16th century onwards, hunting was central to the leisure-time sporting lives of royalty and aristocracy throughout much of Europe. It was a ritualised substitute for the world of military warfare. "Wild beasts", one 17th century writer argued, "were of purpose created by God that men by chasing and encountering them might be fitted and enabled for warlike exercises" (Henry Peacham, The Compleat Gentleman, 1622). In its early days, the courtly monopoly over hunting reflected the mediaeval belief that only the highest echelons of society could be trusted to bear arms and lead armies into battle.

By the 18th century, hunting had come to be associated particularly with the countryside of England, and with a broader range of people. It was no longer the preserve of royalty, but it did remain socially exclusive. To be part of a hunting group, one had to be a landowner or in some other way a man of wealth. The ownership of horses retained its symbolic social status while the traditional red hunting jacket of the 18th century huntsman was a symbolic reminder of the military uniform of cavalry officers.

The Agrarian Revolution and the Fox Hunt

Originally the hunted creature would be the deer. This fine animal was thought a dignified target for royal hunting parties, but by the late 17th century the deer had become scarce in England, as a result of heavy hunting as well as destruction of its natural forest habitat. In the following century, the 'verminous' fox became the target of most hunting on horseback, and has retained this dubious honour up to the present day.

While deer hunting became difficult with the loss of forest areas, fox hunting was encouraged by these changes. In the course of the 18th century, much of rural England was 'enclosed' - that is, its land was partitioned into large farmable fields with the use of walls and hedgerows. Subsistence farming gave way increasingly to farming for profit and, and newly-emerging agricultural methods and machinery helped make these large-scale new farms immensely successful. It was the owners of these farms who formed the backbone of hunting culture.

The newly-enclosed land transformed hunting. Previously it had often taken place within one small area of land, and had been rather static, the huntsmen standing to watch the hounds as they pursued their prey. But now, with large areas of land drained and cleared, and with hedges and fences forming ideal 'jumps', hunting became an excuse for exhilarating and skilful races across long distances.

Early Fox Hunting - For and Against

The swift and intelligent fox was an appropriate target for the new kind of hunting. It was able to run very long distances before it tired, and it remembered the location of its many 'earths', which it would run to in turn, in a bid to escape. The night before the hunt, however, the fox's earths were 'stopped up' to prevent its escape underground. On hunting territories, landowners often planted small coppices of trees to afford the fox a temporary hiding place and to extend the thrill of the chase. But ultimately, the fox was generally caught and killed, and its paws and tail kept as trophies.

Many people in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were critical of fox hunting, although their concerns were not mainly with 'animal rights'. The SPCA was founded in 1824, but most of the anti-hunting arguments of these days revolved around the political connotations of hunting. Fox hunting was seen as the preserve of the conservative and wealthy rural Establishment. It was mocked by radical sympathisers in the towns. Meanwhile, the supporters of hunting continued to argue for its benefits, insisting that it improved the health, kept its participants away from an idle and sinful life, and promoted the manliness and ruggedness required for a powerful society.

Hound Portraits

Foxes were plentiful and were attracted to the livestock of farms, so their numbers had to be kept down by some means. If the farmer were doing this purely functionally, he would use terriers to hunt out the fox below ground. The dog did not require speed so much as a good sense of smell - and persistence. But with the development of foxhunting as a fast sport, hounds had to have speed and stamina over long distances, plus excellent sight. To meet these new requirements, different types of hounds began to be specially interbred to provide these valuable characteristics in combination. As a celebration of these animals, some sporting pictures individuated not only the men and their horses, but the hounds as well. An example of this is Ferneley's Thomas Assheton Smith and the Tedworth Hounds [1588] in which four of Assheton Smith's prized dogs are captured in careful portraits.

Game Shooting and the Game Laws

Another category of sporting art depicts the world of game shooting - the 'game' being a variety of birds (most commonly the partridge and pheasant), and hares.

Shooting animals for sport was even more socially exclusive than hunting. Game laws, in force in Britain from 1671 to 1831, prescribed the range of animals that all but wealthy landowners and squires (slightly lower in the social hierarchy) were allowed to shoot. One of the justifications for the game laws was that they would encourage the wealthy landowner to remain in the countryside and care for the land. Another argument was that, without game laws, the countryside's wealth of birds and animals would be seriously depleted. It seems likely, however, that the main concern was with the issue of gun ownership by the poor. 18th century pictures of landowners (Gainsborough's Mr and Mrs Andrews is perhaps the most famous) often represented the landowner conspicuously holding a gun, a conjunction between wealth, land ownership and possession of arms that would have been rich in meaning at the time.

Meanwhile, in times of agricultural depression, the poor often had to resort to poaching in order to feed their families. But the game laws were rigorously enforced, with the standard punishment being a whipping and imprisonment. One social commentator, travelling rural England in 1820, noted that a third of the nation's prisoners were in gaol on poaching charges - and the punishment could extend to deportation.

Game Shooting and Gun Design

Shooting birds for sport grew out of an earlier, purely functional pursuit of them for food. Initially, traps or nets would often be used to snare the birds and, insofar as guns were used, they were either aimed at stationary birds or fired randomly into groups in the hope of picking off one or two. Using the gun for sport became easier as improved gun design made guns faster, more accurate and more user-safe. But this did not fully occur until the 19th century. Throughout the 18th century, the flintlock gun was used for game shooting. To load this type of gun, gunpowder and metal ball (the early bullet) were put down the barrel, and extra gunpowder was put into the priming pan. When the trigger was pressed, a flint was struck and its sparks lit the powder in the pan. These sparks flew down into the barrel and ignited the powder there, so firing the shot from the gun.

This flintlock design lasted many years, but the guns were difficult to use. Their long, heavy barrels made them cumbersome, and they often failed to fire, the powder sparking in the pan, but not igniting the powder in the barrel. From this comes our expression 'just a flash in the pan'. Another hazard was their disturbing tendency to explode occasionally in the gunman's hand. It was to avoid the resulting injuries that gunmen positioned their hands, on early guns, so far back from the muzzle.

In the early 1800s, the percussion gun was invented and soon replaced the flintlock design. Instead of the flint, the percussion gun used special chemicals called fulminates which explode very easily. The fulminate was placed under a copper cap which led through to the barrel. When the cap was hit by a small metal hammer, it exploded the fulminate and the sparks passed quickly into the barrel - far more quickly than had the flintlock spark - and ignited the powder there. Game shooting was made far easier with this new gun design, and it became a major sport in the 19th century.

Creating the Conditions for Game Shooting

While fox hunting required a countryside of wide open spaces, shooting demanded woodland. In wooded areas, birds could nest and breed and so become plentiful. Just as landowners would sometimes plant out their land with hunting specifically in mind, so they might deliberately create a territory ideal for shooting game. A number of small sheltered woodlands were planted by landowners in the 18th and 19th centuries purely in order to provide conditions for the perpetuation of this sport. Many of the woody areas that appear today to be the result of spontaneous growth are therefore a kind of artificial nature.

Land might be developed for shooting even where the landowner did not have a personal interest in the sport. During a period of agricultural depression, in the early 19th century, it was sometimes more profitable for land with poor soil to be turned over to game-shooting woodland than to be hired out to tenant farmers, as the rents paid by visiting game-shooters exceeded profits made by agriculture.

Coaching and the Arrival of the Railways

One branch of sporting art documents the golden era of coaching. Some of the pictures depict passenger coaches, but many feature the mail coach. These were a familiar feature of 18th and 19th century life, carrying mail all over the country. Once the journey was completed, the coach would be housed and horses stabled at coaching inns. Some of the large city coaching inns were vast complexes which might accommodate up to 400 horses in underground stables.

The mail coaches benefited from the late 18th century and early 19th century improvement of roads. By the 1830s, a mail coach could complete a distance of 534 kms in what seemed the astonishingly fast time of 44 hours, travelling at a speed of approximately 12 kph. But the railways, rapidly expanding between and 1830 and 1850, made these achievements in turn seem trivial. In the course of these decades, the 80 mail coaches once leaving London daily had dwindled to 11, their work taken over by trains.

|

Click here to view all sporting art

Alfred Munnings, Son-In-Law, 1927, oil on canvas

Alfred Munnings, Tiberius, oil on canvas

George Stubbs, 'Firetail' with his Trainer by the Rubbing-Down House on Newmarket Heath, 1773, oil on canvas

|